The child's earliest memories were of her father's tears and her mother's ghost.

Still, in a short time her father learnt to replenish himself with ale and her mother died yet another little death; Ysabella watched helplessly as time stole the lady's face from the child's memory. Only the words remained. Ysabella swore to remember her promise to her mother, though she could remember little else of her.

She was fifteen when her father told her that she needed a mother. Ysabella protested that she already had one. The next day her father went away on business and she spent the time he was gone scrubbing and cleaning their home, wanting to show him that they were not left wanting. She worked until her fingernails were charcoal and her face ash, and she was in this state when her father returned with a woman and two children by his side.

The lady commented that Ysabella was filthy, eyes boring into her dark complexion beneath the soot. She took a hand of each of her children and dragged them up the stairs, leaving Ysabella alone with her questions and her father.

Briskly, he spoke. “That is my new wife, the Lady Greer. You must teach yourself to love her because I have asked it of you.” Ysabella shuddered by her father's side for both the lady and her daughters had looked cold and severe, but she remembered her promise to be dutiful, and asked:

“How am I to love them, father? I love only you, that has always been enough.”

Her father bent beside her, warming his hands by the coals. “You must learn to love them piece by piece,” he said. “That is the only way to love.” He explained that his new wife had loved first his purse, then his title and that the rest had followed. At his words Ysabella tried to learn to love her new family bit by bit.

She loved her stepmother and the eldest daughter, Alyth, for their absence. The week of their arrival they had been an unavoidable force as a parade of dressers, silks, brocades and jewels moved into Ysabella's home, working their way into long empty corners and long forgotten nooks; however, the storm of them gradually diminished. Soon they were out most nights, attending endless parties throughout the kingdom. Her stepmother had explained that Alyth was to become a woman of society and that it was important for her to be seen with the right people in the right places, and Ysabella dared question her no further in case she brought about the end of these cherished reprieves.

That left the youngest, Mysie. Ysabella would study her during long periods of silence, time they would spend reading in one another's company, sometimes by the fire, sometimes in their sprawling garden. At first Ysabella mistook the quiet of her stepsister for coldness, believing the girl would not deign to engage with her, but once she took her father's advice and started to look not at the complete puzzle but at the pieces she began to understand.

They were forced to share a bedroom. Ysabella's father had built a property under the belief that the size of a room was a true indication of wealth, not the number of them a house held. Alyth insisted that she should have her own space, being seventeen and on the cusp of something or other; Ysabella often tuned out the specifics for the sake of her sanity. Mysie and Ysabella spent their first nights in silence and as such Ysabella did not notice Mysie's noiseless tears for many weeks.

Moonlight betrayed Mysie in the end.

Moonlight betrayed Mysie in the end.

“Sister, why do you cry?” Ysabella asked the first night she saw the water leak upon a plump pillow. Mysie had no words; she turned to face the far wall and they both quickly gave themselves to sleep.

Ysabella asked her question each night for a fortnight and each night she was met with silence, until finally:

“Sister, why do you cry?”

“This bed is too big,” Mysie said. “This city is far too big.” And in a moment Ysabella realised that she had considered nothing but her own feelings since her new family had moved into her home. They had merely been not there and then there; she had never considered the there they had left behind.

Then Ysabella loved Mysie for her stillness, a quiet that was so different to the shattering racket that accompanied Alyth everywhere, different further still from the excluding silence that Ysabella's stepmother used as a weapon. Mysie's quietude was calculated, considered; she spoke only when she felt she had something worth saying, unlike her sister who tried to fill all silences to the very brim with any word she could grasp between her slender fingers. Alyth spoke to speak; Mysie spoke to be heard.

Then she loved the shape of her. The others were all corners and sharp angles but Mysie was made of pillows. She was rounder than any of them, her stomach curved and protruding, but she carried herself in a way that made it seem as though she took up less room than anything in the house, commanding spaces to fit comfortably around her. She made her own girth convention so that it was those around her who were lacking, not she who had overindulged. Ysabella grew to love her scent, the lingering aroma of fresh bread that hung to her every fold. She loved her hair, so red that flames shied away from the light of it. She loved the dexterity of her hands and the artwork she made with them. She loved her candour. As Ysabella's father had instructed, she learnt to love her bit by bit.

“You have charcoal on your nose,” Ysabella laughed once, one twilight, and she pounced before Mysie could stop her, rubbing the evidence of her art from the bridge.

Mysie chastised her, “Still Ella, still,” though there was no real vexation there.

Ysabella lay by the burning furnace as her stepsister became lost in concentration, sketching Ysabella a smudged brow. The stone floor scratched at Ysabella's back but she tried to mimic Mysie's natural serenity as the girl drew. Wildfire danced across Mysie's face.

“When you came here, I thought you were cold,” she told Mysie. They were sixteen now, left to grow together by a father who chose to drink ale and a mother and sister who chose to suckle the teat of commerce. Bit by bit, piece by piece. Ysabella cherished these moments where they were free of the interlopers who disguised themselves as family. The house warmed.

“And now?” Mysie said, her focus shifting from parchment to model.

“Now you're fire,” Ysabella said.

Mysie's eyes smiled behind half moon frames.

In that moment, at last, Ysabella grew to love those tawny eyes that were a perfect mirror of her own. She thought, this is it. This is the final piece.

That night as they went to rest Ysabella found herself overcome by a sadness she could not name.

She did not have Mysie's quietness so she tried to muffle her gasps against the pillows; not even the layers of cushion could disguise the sound. She could not remember crying before. Each time she had felt the inclination in the past she had leaked words instead of tears, a torrent of words. Now there was only water.

She did not have Mysie's quietness so she tried to muffle her gasps against the pillows; not even the layers of cushion could disguise the sound. She could not remember crying before. Each time she had felt the inclination in the past she had leaked words instead of tears, a torrent of words. Now there was only water.

“Sister?” Mysie's voice crept along wooden boards.

Ysabella bit down on her tongue so hard she feared she may bleed.

“Why do you cry?” Ysabella felt Mysie's weight press against the bed, against her quilted thigh. Her hands petted Ysabella's pitch black hair, whispering soothing platitudes with her fingertips. Ysabella allowed those hands to guide her onto her back, was forced to confront the kind face she had grown to know every line of. She clasped a hand to her chest, nails working into the skin of her left breast. “It is too big,” she managed to say between mewls. “It is far too big.”

Mysie laid her hand against Ysabella's, holding it reassuringly with her own. Ysabella's heart beat against their interlocking fingers. Without making a sound Mysie told her that she understood, and then she taught Ysabella the secret of her silence. She pressed her claret lips first against the forehead, then the bridge, then the cheek, and on. With each touch Ysabella's tears quietened. Mysie stole the noisy sadness from her with muted caresses.

Ysabella in turn welcomed the young woman's touch. She allowed herself to feel the warmth she had shied away from, opening herself to the licks of Mysie's flames. She drew Mysie beneath the sheets so that the velvet tipped, hugging their bodies. The bed that had often felt too big at once seemed to fit them like a custom-crafted slipper.

Soon Ysabella found there were still hidden parts of Mysie left to love.

They had happily thought themselves abandoned, not knowing that the Lady Greer's nature gifted her with an ability to see around corners and behind closed doors. She had a suspicious quality to her, one that fed her gaze and allowed her to see not only what was but what could be. This distrust of all she met enabled her to note the change that had come over her youngest daughter since they had moved, allowed her to lock away each secret look and each cautious smile. The closeness of the girls was a constant source of irritation to the woman, though the strain of it wormed itself so deep within her that it could not be read upon the shadow of her face.

She despised her stepdaughter for the shame of their association, the whispers that followed her at balls. She heard what they called her, that slur: mother of the cinder child. The words echoed against the skull with every step she took, cinder, cinder, and she hated the cinder child, despised her husband for keeping the truth of it from her. That he had brought his wife back from his travels overseas, that she had bore him a cinder child of her own likeness, that had held no significance to him. That careless lush, Greer thought, resentment dribbling through her, too drunk to hear the whispers, too blinded by ale to recognise that his child was unnatural, a child of the ashes. But Greer saw. She knew that the child's darkness would muddy her own if she was not careful, so she watched. She listened.

And then one day, she saw.

She was not surprised when she found them sharing one bed, her daughter's arm resting upon the night child's unblemished skin. What did disconcert was how fiercely she felt the rage swell within her, crashing against her ribcage. It was so loud that it woke the sleeping girls, though Greer had not made a sound. Her stepdaughter bolted up, springing to life in an instant. Her movement caused her nightshirt to slip and reveal a shameless breast; it mocked Greer with its pertness, the near untouched blush of it. She began to tell tales of being cold in the night but Mysie's silence told her mother all that she had already known. Her daughter had not yet learnt to keep her thoughts from her face. No mind, Greer thought, it shall come with time.

She held a hand to hush her stepdaughter and said:

“Your father is dead.”

She turned to the door and was set to leave but the compulsion to look back at the girls once more overwhelmed her. Ysabella's mouth was agape. Mysie had not moved.

“We are ruined.” Greer spat her parting shot. Then she walked away and left the girls to their silence.

They were left enough money to maintain the estate and their current lifestyle, though they all knew this would not last further than the year end. A lot of their money had been spent on her father's daily dose of poison and for the first time Ysabella resented her father for his affliction, his demons, his cowardice. She knew now that he had died with her mother, that she had raised herself alone.

She wanted to rage against her stepmother, to rain down the anger she felt towards her father for leaving her under the woman's control, but she remembered her promise to her mother:

Be obedient.

So she tried. She tried when Alyth began to call her Cinder Ella to her face, muddying Mysie's pet name for her with slurs Ysabella had often heard cast at the local shoemaker and his son. Never before had she made the association, never had she realised that people were using the term as a knife. Inside she rallied against the poison of it, for Tom the shoemaker and Wilhelm his son, for her dead mother, for herself.

But the words, the words: dutiful, obedient, kind, dutiful, obedient...

And so she tried. She tried when her stepmother took away her fine clothes, her few precious stones, needing to sell them for the good of the family without Alyth or Mysie having to pay a similar penance. She tried when Alyth and her mother found themselves in the house more and more often, eyes following Ysabella through every room, into every private place. She tried when the Lady Greer piled throws and rags beside the fire in their kitchen, when she promised that Ysabella would never find herself cold in the night again. At first Mysie protested, offered to sleep there instead, argued that it had been Ysabella's bedroom first and that it should be her room to the end, but in time she was worn, beaten, tired. Her mother broke her with a quiet violence, using the girl's own stillness against her. Soon Mysie gave herself to laconic despair.

Ysabella wavered then, her resolve shaken by her companion's reticence. The girl no longer shared with her, not her words or her quiet. She crawled within herself and Ysabella recognised it, had seen the same thing happen to her father when he had lost his love. Her fire waned. The worst of it came when she became cold, treating Ysabella as though she were a stranger to her. That was harder than Alyth openly scorning her or than her stepmother treating her as though she were a maid. It was Mysie's quiet, the first thing she had loved of her, that truly injured Ysabella in the end.

The girl gave herself to cinders and ash, but that is a story you are likely to have heard before.

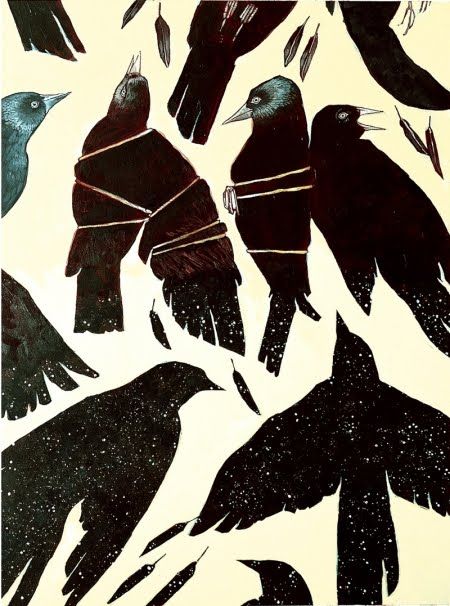

There was to be a ball. There was to be a prince. Alyth and Mysie were to be paraded, sold. Ysabella's invite was lost to the hearth. They were taken and she was left with rodents, birds, frogs and toads, her only company. For months she had laboured, she had fallen, she had remained obedient, the word rattling inside her mind, never relenting. She escaped to the garden, the one place her stepmother and sister never found her because they were afraid of the nature of it, the very life it held. Ysabella wanted to weep but she could not find the tears. She wanted to cry out but she could not find the words. She managed a weak moan.

“Hush, child,” the voice came, deep and firm.

Ysabella spun, trying to ascertain the source of the words. She was alone but for the plants and her animals. The blackbird she had come to know as Branwenn circled just above her, near invisible against the dark sky. It landed on the soil before her and its shadow grew, twisting and changing into that of a slender woman, the shape of her dancing on the moonlit stones.

The bird woman began to speak of godmothers and wishes and promises and curses and the words washed over Ysabella like silk. A pumpkin turned into a carriage, frogs and toads turned into footmen and drivers, mice transformed, birds turning into distortions of their former selves. It is a magic that is well-known. Branwenn's final words, “Fly, little bird,” chased Ysabella along clouds.

A ball. A prince. A young girl walking on glass.

“Dance with me?”

“Yes, my prince,” she said with a smile, allowing him to guide her alongside the music. He spent each dance of the evening pressed against her, much to the dismay of his advisers. All eyes followed them as they waltzed between guests but there was only one gaze that Ysabella thought of, her own eyes searching out those that were a mirror of her own. She could not find her, though she did meet Alyth at one point. The girl recognised her, of course she recognised her, but the brazenness of Ysabella's act overrode Alyth's good sense. It could not be her, the cinder child, this gilded beauty who had captured the attention of the prince. Denial is magic of a sort. It could not be, her head told her, so it wasn't. Her face was contorted, hateful. It was the first time Ysabella had seen her stepsister look truly ugly.

He loved her immediately, or so the prince cooed, dragging her from the lights and noise of the party to the suffocating solitude of the balcony. A name, a name, his sweet needed a name.

“Cinderella,” Ysabella said without thought, wearing her scars as armour.

The scent of pumpkin clung to her clothes.

“Sweet Cinderella,” the prince smiled, and it was not an unpleasant smile, though a trifle foolish.

Ysabella remembered her promise to her mother: always be kind. She entertained him. She told him stories, obscure little stories, and on occasion he laughed in the right places. She charmed him with little lies, fantasies about the riches and happiness she had left behind. She played the game and for a while it was effortless.

But as ever, all that is pretend must come to an end.

“Why do you love me?” she asked with lowered brows.

“Because you are beautiful,” came the reply, and it was the one that she had expected.

“But what of me is beautiful?” she tried. She wanted to know the bits and pieces of it all. The prince faltered, he would not, could not answer. She was no different to the paintings in his great hall: beautiful, untouchable, to be gazed at, enjoyed, but not engaged with. Not known. It was not his fault, she knew. It was just not the way she had been taught to love.

The clock struck and the game was at an end.

She fled for the sake of them both, leaving behind only one slipper, a token, an apology. She fled to her garden, to her haven. She heard her family return home a little after two, heard her stepmother lost to her own suspicions as she stalked to her bedroom, heard Alyth whining about a stranger who had monopolised the prince. She felt Mysie before she heard her, felt the eyes she had sought out all evening as they took in her now tattered dress, her bare feet.

“Did you enjoy yourself tonight?” Ysabella asked once the silence became too thick, finding shelter under the great tree. There was an edge to her voice, one she had not anticipated, but Mysie's response when it came was playful.

“Not as much as you did, your highness.”

Ysabella allowed herself to turn then, to look upon the face she had missed so. There you are, she thought, exalted. There you are.

“Do not tease,” Ysabella teased. “I would make a wonderful queen. Did you not see how expertly I managed the chain dance? My blood runs blue. Bluer than my frock,” she finished, forgetting her gown had muddied at midnight.

Mysie, no longer lost within herself, no longer wilting, opened like a flower. “You daft arse,” she laughed. “You could never be one of them. You are too uncouth. Your mouse is more refined,” she said, and at the words the littlest of the lot looked up from the smashed pumpkin it had been gnawing on, allowing an offended squeak.

“My servants will have your head,” Ysabella said, and then because she could not help herself, “What has brought about this change in you? I thought I had lost you.”

“I was lost.” Mysie looked wounded then, abashed, ashamed. “I thought that they would feel less threatened if I were to distance myself from you. I thought that they would relent, treat you better. I was foolish.” Mysie came closer, stood in the path of moonlight that fell on branches and stone. “I thought I could pretend.”

“And I,” Ysabella said, eyes dancing. “Tonight. I thought I could play a princess but I couldn't. Nobody can walk on glass forever.” Then, with a smile, she glanced at her own nude feet. “I could not even do it for one night.”

She laughed then, a laugh that promised both joy and tears. Mysie joined her against the tree and together they revelled in the nakedness of the moment.

The prince found her within two days. He scoured the kingdom and the citizens pointed him towards the Lady Greer, towards her two haughty daughters and the girl they had covered in ashes. Despite the protestations of the youngest sister, despite the mother's glares, he found the girl in their garden and he forced a glass slipper upon her foot. It seemed to him that it joined her perfectly, though she claimed it hurt, that it was not the right fit.

The modesty of her. He knew he had found his queen.

The mother made no comment. The eldest daughter moaned, it could not be, it could not be, why her and not me, why her? The youngest became positively wild and had to be restrained by the prince's loyal footman. She threw curses at him like they were spears and the prince pitied his love, was enraged on her behalf as he eyed her oppressors. He thanked his gods that he had found her, that he had saved her from these monsters.

Still his love, ever dutiful, ever obedient, ever kind, still she approached the wild girl with the hair of fire and rested her hand upon a bare arm, whispered secret words into her ear. The prince could not hear any of it but his sweet queen's promises tamed the beast; the queen's stepsister fell silent, her eyes resigned. My selfless girl, the prince thought to himself, even now she pities those who have belittled her, those who forced her into rags and grime.

Then, without another word, the girl followed him to his castle.

She blamed herself. She had let the prince fall in love with her lies and now she was to be punished. She allowed herself one small mercy; now she could support her family, the lot of them. Though they had treated her poorly Greer and Alyth were still of Mysie's blood and she would treat them accordingly. Her new position opened her to wealth, to some power, and she would not waste it. These were the condolences Ysabella allowed herself during that first week leading to the wedding and the coronation, a week that was a whirling mess of ribbons, gowns and gifts.

It was at the ceremony following the wedding that the prince made his greatest gift known to her.

“My love,” he began, “You are dutiful and you are obedient and you are kind, and as such you have pleaded for the life of your family, though they have derided and demeaned you. Their life I have granted them because it is what you desired. But you are new to the ways of the court, you are pure and good and you do not understand that kindness is not always repaid in kind. This lesson is my gift to you.”

The footman approached with a box, a green velvet box. Guests chattered amongst themselves.

“Your stepmother and sisters have been banished from the kingdom, given a home in the borders,” the prince continued as Ysabella fingered the clasp. She did not want to open it, her intuition screaming, but she knew she must. “They will live in peace because it is what you have asked of me. But first, my queen, they were sentenced to the birds.”

Ysabella opened the box. She closed her eyes when she saw theirs looking back at her accusingly.

“Two from your stepmother, who by rights should be dead, and one from both sisters, plucked from each ugly head,” the footman waxed, then he giggled at his own rhyme. The prince was proud.

“You will come to love the law of the land because I have asked it of you,” he said, and Ysabella found herself smiling back at him, unable to stop herself. Relief flooded through her and she could not stop the grin that took command of her face, could not deny the joy that threatened to reveal her secret.

Four eyes in a box and not one of them resembled her own.

Ysabella knew she should pity her unseeing stepmother, her sightless stepsister, but too much lingered; she suspected that Alyth had been blind long before Branwenn plucked out both of her eyes. A final gift. The prince only saw wholes, not the bits and pieces of people, so he did not recognise that the eyes before him were all made of teal. There was not a fleck of chestnut amongst them. Ysabella saw and she could only smile. She is safe, she is safe, the new mantra replaced the old, her mother's words at last following her face to a place beyond memory, beyond significance.

She is safe.

There were many rumours following the wedding: tales of girls chopping off toes and heels, stories of midnight curfews and ugly stepsisters, of glass slippers and a girl rising from the ashes. Ysabella, the Bird Queen, the Phoenix. Queen Ysabella, the bird on fire, a fire that cast warmth and light across the entire kingdom throughout her reign. Ysabella ignited.

And now, reader, you know the source of her flames.

You must learn to love them piece by piece is one of my favourite lines of anything now. Well done, sir. Also, should we just admit this blog will be all lesbian love stories?

ReplyDeleteThat is all I have to bring to the table, I can't lie.

DeleteI loved 'the licks of Mysie's flames'. Excellent work, Van Dick.

ReplyDeleteThank you for reading.

Delete